By Kristen Scott

Kristen Scott is Managing Partner and Senior Principal of Weber Thompson where she heads the Workplace studio. As Managing Partner of Weber Thompson for more than 25 years, she has overseen the growth of the firm from its beginnings to the sustainably focused 60 person multi-disciplinary firm it is today.

It’s hard to believe that it has been twenty years since we designed The Terry Thomas, our first office building in South Lake Union. At the same time, it’s interesting to reflect on how our approach to sustainable design has evolved since then, ultimately leading to our move to Watershed, a Living Building Pilot project.

The Terry Thomas, Seattle, WA

Part 1: The Terry Thomas

We started the design of The Terry Thomas in 2004 when LEED was just emerging as an aspirational program. We wanted to show our clients how practical and affordable high-performance building design could be and how they could incorporate it into their market rate projects.

After internal discussions with staff, reducing energy usage and having operable windows were at the top of the list along with maximizing daylighting. We were coming from an older concrete building with a failing HVAC system and poor access to natural light which clearly influenced our vision for the new office.

Passive Ventilation and Cooling

Twenty years ago, operable windows in modern office buildings weren’t really an option. Buildings were mechanically controlled boxes, sealed to minimize energy usage and protect occupants from outside weather; heated in the winter, cooled in the summer to be at an optimal 70 degrees year around. Questioning that mindset drove one of the biggest design moves of The Terry Thomas.

Our most audacious idea answered both our employees concerns and the tight budget. Could we remove the air conditioning system and still create a comfortable workspace? It would save us about 4% of our total construction budget which was good, but we’re Seattleites. Anything over 78 degrees and we’re sticking to the trace paper on our drafting boards!

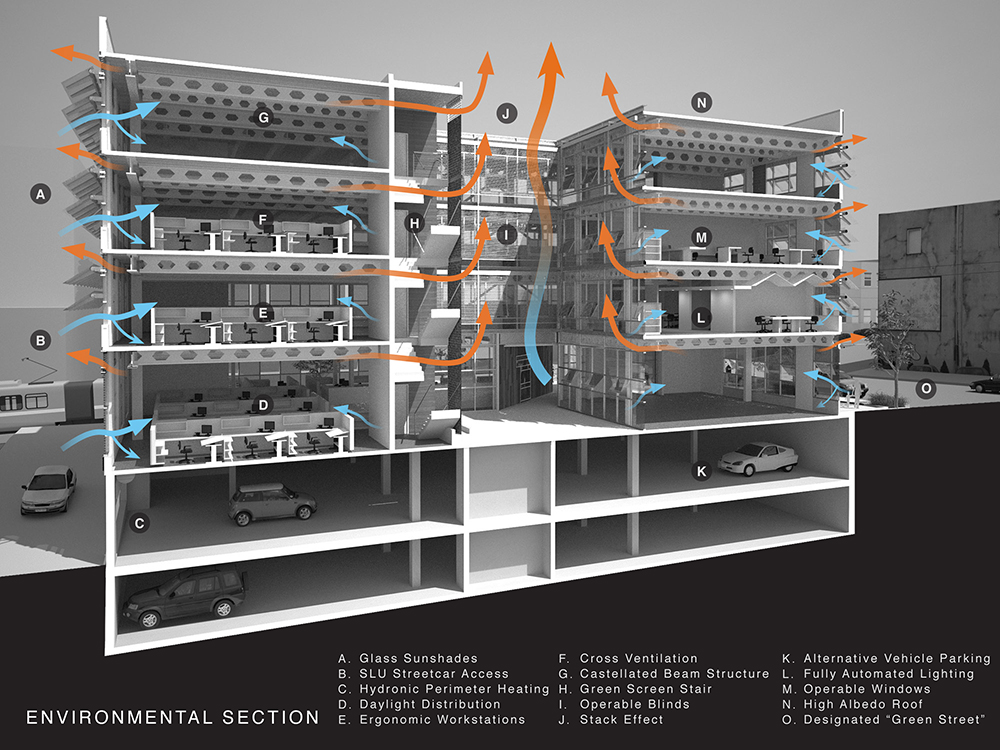

The team explored many ways to optimize the balance between heat gain and daylighting while minimizing energy usage to identify the best design strategies. Passive ventilation (with no air conditioning) became a real option with an internal courtyard working as a chimney to draw air through the building on hot days.

Balancing Heat Gain and Daylighting

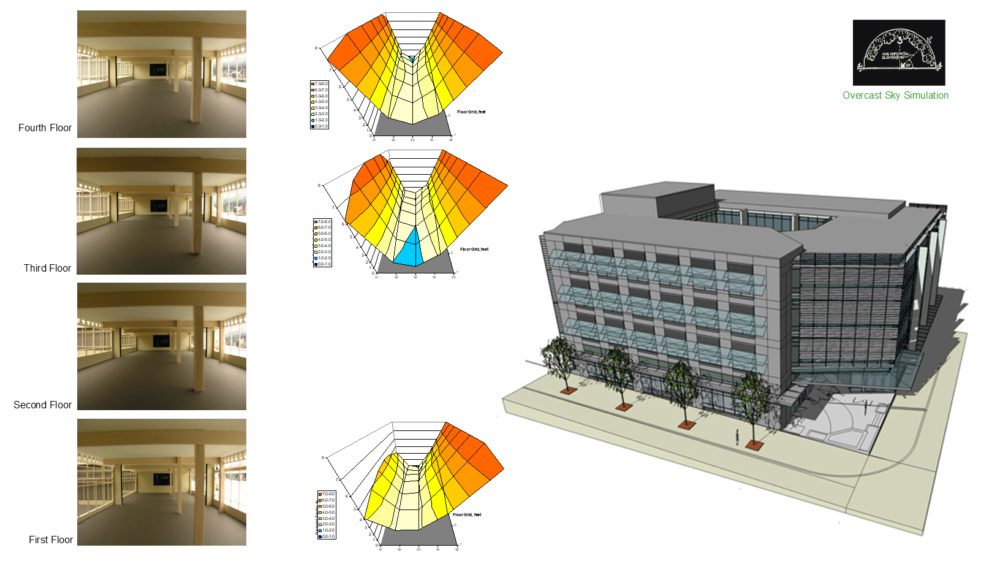

Thermal modelling allowed us to fine tune our strategies to minimize heat gain from the sun. The predictive studies showed that by utilizing a combination of several strategies, there would only be about 20 hours per year where the space exceeded 85 degrees in the late afternoon—that didn’t sound too bad!

Fixed shades on the east and west, along with automated blinds on the south facing courtyard façade and automated louvers around the exterior of the building and around the courtyard for ventilation and to provide a night flush, made it work. This both saved the energy usage of a mechanical air handling system, and the head height needed to run it, reducing the floor-to-floor (FTF) heights to a more cost effective 11’ FTF.

The courtyard in the center also created shallow floor plates—at just 38’ from glass to glass—resulting in over 95% of the floor area meeting the natural daylighting requirements of LEED.

Daylighting graphics by the University of Washington’s Integrated Design Lab

Removing AC resulted in 56% lower energy usage than a typical office with a measured EUI of 37 after occupancy. Typical office buildings at the time had a measured EUI of 68-80.

Beyond working to ventilate the building and provide additional daylighting, The Terry Thomas courtyard also acts as a social and a direct connection to the outdoors.

Walking through the courtyard to get to the lobby and having open windows almost year round, means tenants are constantly aware of outside temperatures and weather conditions. This creates a natural feedback loop that influences occupant’s behavior and awareness while also providing the biophilic benefits of being immersed in the natural environment.

Climate Change Impacts

Unfortunately, by 2019, increasingly warmer and smokier summers with unhealthy levels of fine particulates in a naturally ventilated building became a growing area of concern, contributing to the decision to move to Watershed, our Living Building Pilot project in Fremont.